Turning girls into

game-changers.

Watch our video to see how we use lacrosse programs, teams and tournaments to build strong women.

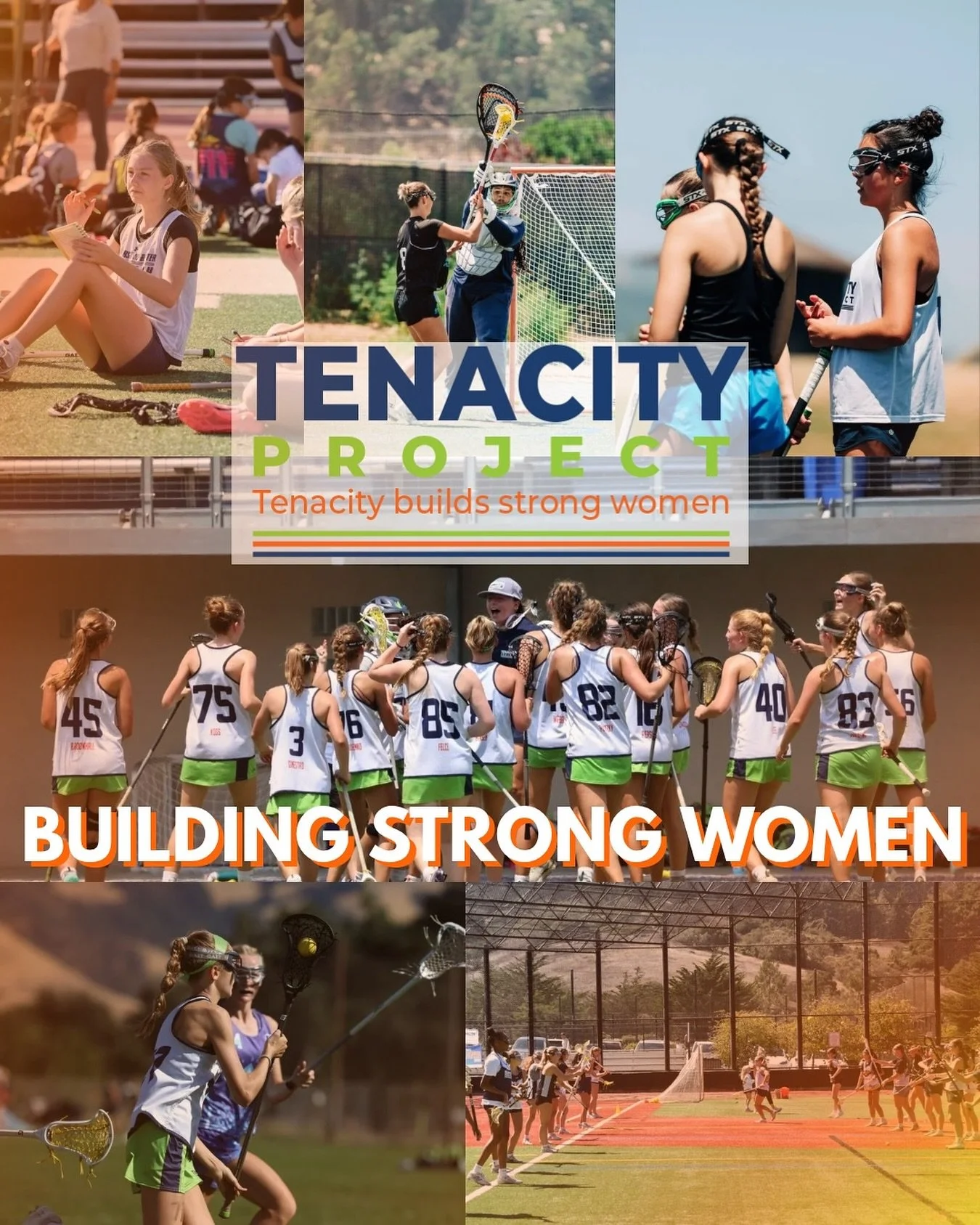

Tenacity builds strong women.

Founded by Theresa Sherry—Princeton alumna, championship coach, and Hall of Fame athlete—the Tenacity Project uses lacrosse as a platform to empower girls and young women.

Core to the program is the Tenacity Way, a unique, holistic approach that emphasizes well-being, mental toughness, and personal growth.

Tenacity has impacted thousands of athletes nationwide—500+ of whom have gone on to play in college—helping them grow into resilient, confident leaders on and off the field.

❊ The Tenacity Way

How we do it.

Skill Building & Game IQ

At Tenacity, skill development is driven by world-class coaches who have competed and led at the highest levels of collegiate and national play. Our athletes learn the techniques, decision-making, and competitive mindset that unlock their potential—while growing as leaders in every part of their lives.

Mental Toughness

Tenacity helps girls build mental resilience by giving them tools to understand their emotions and manage pressure. Through guided journaling, reflection exercises, and supportive coaching, athletes learn to stay centered, confident, and connected to who they are—on and off the field.

Leadership Training

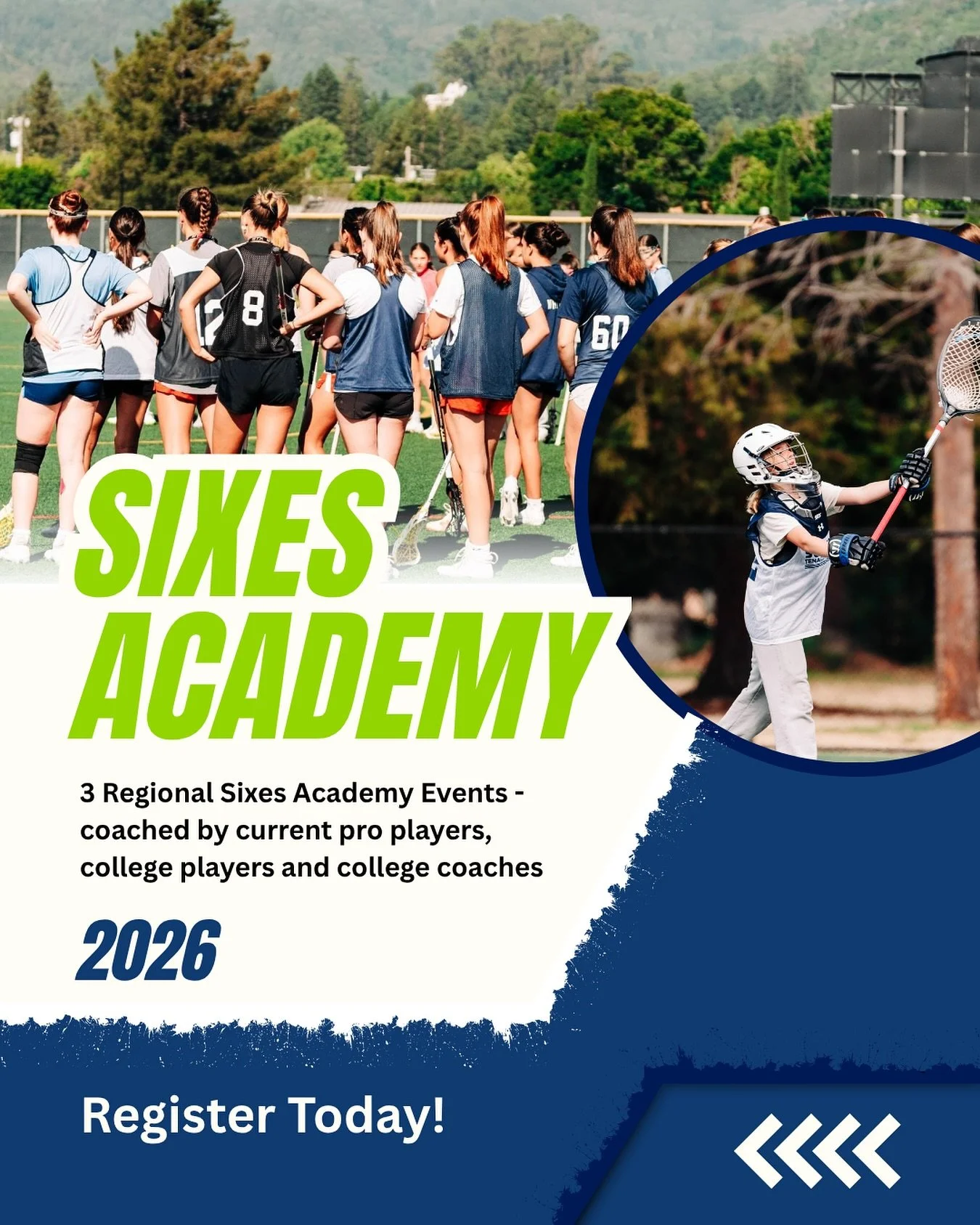

Tenacity grows leaders by giving girls real opportunities to step up, speak up, and shine. Through a collection of regional events, tournaments, and virtual leadership workshops, our athletes practice communication, collaboration, and decision-making in supportive, coach-led environments.